Late June batch of links replaced by my published essay about therapy

Last Fall, I went to see “A Real Pain” in theaters and really loved it. I texted two dozen people the next day to let them know they should see it, too, and few of them had any idea what it was at the time. A few months later, when it was available on streaming, several of those same people texted me to say they’d watched it - and wanted to speak about it with me after they had. It meant a lot to me that they followed up how and when they did, making my thoughts feel welcomed and my recommendations appreciated. I also got the sense that they were less moved by it than I was, and their interest in hearing about it from me was more a love language for me than it was for cinema.

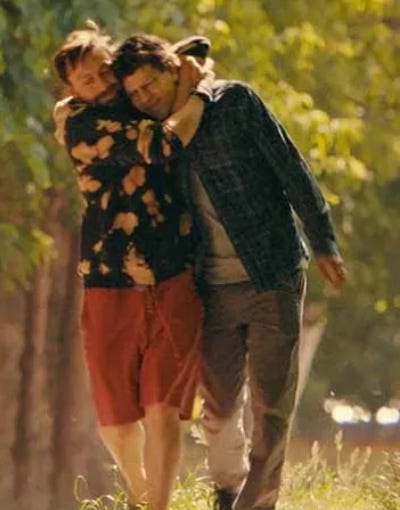

While the movie is full of memorable scenes for me, even after all this time, the scene that I couldn’t stop thinking about and then rewatching this year is a one-minute clip below. For most who saw the movie, this scene wasn’t near the top of what they remembered and retained from the film, which takes place in part at a concentration camp in Poland. For me, though, the brief scene near the beginning of the movie encapsulated a lot of me and my adolescence, as I was figuring myself out and where my strengths resided with regard to others.

Around the time I saw the movie, but unrelated to the movie itself, someone proposed that what I carry with me and convey to others can be both a strength and a weakness. I responded that I don’t view any of it as a weakness these days, that the strength I have is my attentiveness to others at a level some wouldn’t recognize to activate without be summoned to service. That whatever trauma I possess at this time is best dealt with by channeling it into activism on behalf of the next person going through something similar in real time.

Accordingly, on the phone recently with an old college buddy, I pointed out that for so many when they discover friends of friends are struggling, it’s easy to opt out, citing how if that person wanted to speak with them directly, they can reach out. We all know that the third-party never will reach out, absolving the speaker of having to be a thinker or a comforter. For me, I run toward those fires, making myself available to them beyond what would ever be asked from me. I want to show up when an access road is available to me - to anyone. Because, as Benji says in the clip, “No one wants to be alone, Dave. I’m going to check it out.”

Around the same time I saw “A Real Pain” on screen, I decided to write an essay about my therapy journey across recent years. The essay went through several drafts, and it turned into a piece of writing that I am very much proud of, arguably the best personal essay I’ve written to date. The best personal writing is both personal and universal at once, and it’s my hope that you’ll read it and, in doing so, see some of yourself within my story the way that I did in Benji’s.

Early this year, I was extremely moved by the compassionate act of some college students who turned up at the door of their ailing professor, to check it out. I delivered a sermon earlier this month on the subject. After I give my annual sermon, one of the people I send a copy to is a man in his 90s, a member of our congregation who since Covid-19 set in hasn’t returned to the synagogue. Ordinarily, this man replies to my emails straight away, with praise for the message and support of me. But this time around, Sunday and most of Monday went by without a reply. I decided I should check it out. Although I don’t know his daughter, I know who she is. So I researched where she lives locally, and I showed up at her door. To make sure. To be sure.

She let me know that she had spoken to her father earlier that same, that he was fine. I was relieved. I headed home. The next day, I received my coveted email from the nonagenarian. He wrote, in part, “Our daughter Linda and Helen and I are amazed that you remembered where Linda lives and that you made contact with her. It was good making contact with a long-time friend of the family. We wish you well and thank you again for making contact. Keep writing.”

Since I’ve known this man, he always ends his emails with “Keep writing.” In the past, I have interpreted that line as fuel, writer to writer. He is many decades retired now, but was a proud writer in another era. This time around, though, I read his signoff differently, more so as a request to remain in touch. I intend to. Hours after reading that message, and interpreting it differently than I have in the past, I left a lengthy voice mail for my 17-year-old niece about how young people have a spidey sense to check things out, to check in on people, to be available, and to show up. And as people age into adulthood, they lose that spidey sense in the name of time and responsibility, and they drop completely that notion of knocking on a door, citing sensitivity and privacy. Often, not always, they cease to do the right thing, to be there for someone who is alone, in body or in spirit.